When north Cornwall residents’ water turned black and gelatinous in 1988, they were urged to mix it with orange squash when drinking. This powerful film lays out the effects of the toxic H2O – and their long struggle for justice

It is becoming a cliche to liken issues-based TV dramas and documentaries to Mr Bates vs the Post Office. Nevertheless, you get the sense that Poison Water is hoping to do for communities affected by the shocking inaction of the water industry what ITV’s hit did for the subpostmasters wrongly criminalised because of a software glitch. A damning one-off, it tells the story of Britain’s biggest mass poisoning and the apparent greed and incompetence that has meant it has loomed large in victims’ lives ever since. There are also parallels with the recent drama Toxic Town, and the continued fight for those affected by poisonous waste in Corby in Northamptonshire.

We open in the summer of 1988, when residents in several towns and villages in north Cornwall noticed something strange about the water coming out of their taps. It was blue in some cases, black in others, and could be gelatinous or sticky. It was also accompanied by a rapid outbreak of ill health, from vomiting and diarrhoea to rashes, blisters and severe headaches. For some, the effects were temporary, but many people went on to have long-term health problems, and there were even premature deaths that families are convinced were caused by the water they drank and bathed in that summer. Water that – because of an error at a treatment facility – had been laced with toxic amounts of aluminium sulphate. It would take more than two weeks for those in power to admit there was a problem. In the meantime, residents were told the water was perfectly safe, and to mix it with orange squash to improve the taste.

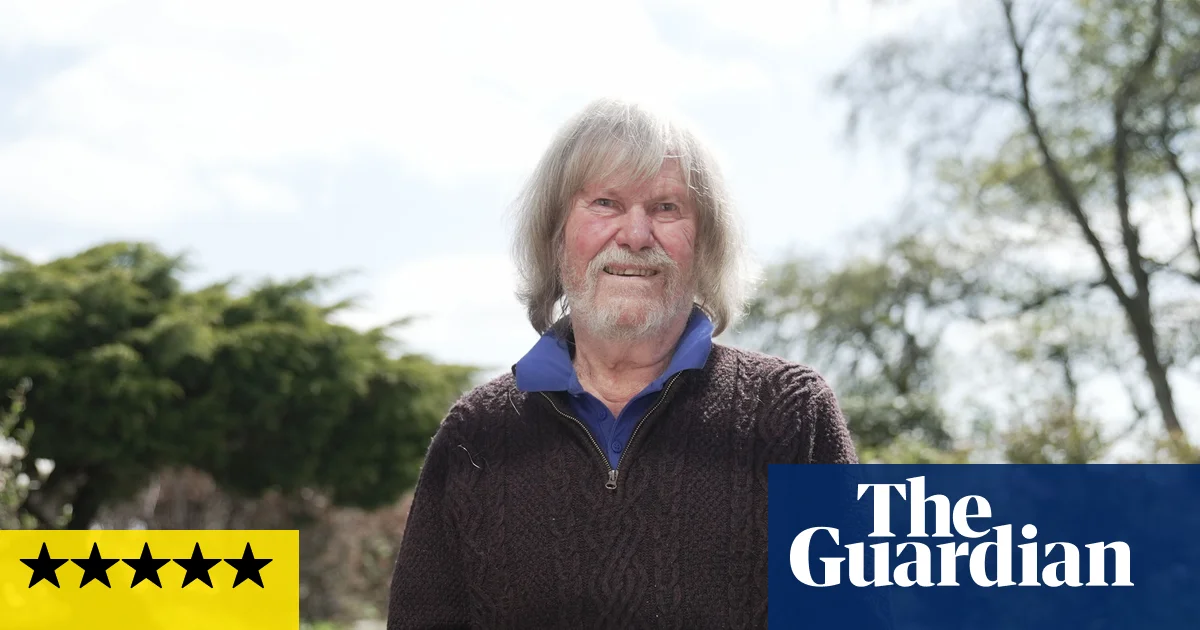

Carole Wyatt, a resident of the sleepy village of St Minver, says she didn’t want to speak about the poisoning again. Thank goodness she changed her mind, as she quickly becomes one of the programme’s most outspoken interviewees. There’s blooper-ish humour as Wyatt urges the programme-makers not to edit her down like they did on an episode of the BBC’s Horizon at the time, and to keep in the “good bits”. Things quickly become less droll, as she explains what she wants them to preserve. “Miscarriage of justice, I want that in … before I die I want this truth to come out.” As we learn, justice has indeed been scant – bar a government apology – with calls for a public inquiry unanswered in the intervening years.

Poison Water relies heavily on that Horizon episode and other archive material, and there is a risk that the final product could feel more like a repackaging than an original piece. Naturally, though, taking a four-decade step back from events casts them in a different light. And there are enough new interviews here – with residents, experts and politicians – to bring the whole thing startlingly, discomfitingly into the present. Among those interviewed is Michael Howard, then minister for water and planning under Margaret Thatcher. He is shown a letter obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, in which an employee of the water inspectorate had urged the government to go easy on the whole thing, lest prosecutions “render the whole of the water industry unattractive to the City” (this was at a time when the government was preparing for the privatisation of the water industry). Howard says he isn’t sure he ever saw the letter. “I hope you’ll emphasise that it was a long time ago and I can’t remember,” he adds. He strongly denies any suggestion of a cover-up or collusion, describing it as “a terrible mistake which should never have happened”.